THE CHURCH OF THE JACOBINS

Tori Schmitt

- Y. Christ, Eglises parisiennes actuelles et disparues, Paris 1947. Cited by Sundt in “Mediocres domos et humiles habeant fratres nostri,” p. 397.

- Rechac (La Vie du Glorieux Patriarque S. Dominique), a Dominican Frier cited by Sundt, “Toulouse,” 203.

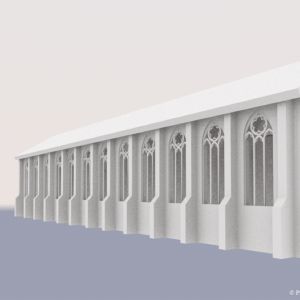

- see figure, Convent of the Jacobins, fragment of tracery from chapter house (Musée Carnavalet).

- Y. Christ, Eglises parisiennes actuelles et disparues, Paris 1947. Cited by Sundt in “Mediocres domos et humiles habeant fratres nostri,” p. 397.

Sources

Most of what is known about the church’s visual appearance comes from Alexandre-Albert Lenoir’s Statistique Monumentale de Paris: Explication des Planches and Georges Rohault de Fleury’s Gallia Dominicana: Les couvents de saint Dominique au Moyen Age, two architectural surveys published in 1867 and 1903 respectively. 6 As the church no longer stands, the modern understanding of the church is mediated through these sources rather than through direct contact with the church. Each of the two sources depict the Jacobin Church with a different viewpoint. The Statistique Monumentale depicts the Jacobin Convent in the process of it’s dismantlement, whereas the Gallia Dominicana, published 50 years after the destruction of the convent, provides an overview of the church as a complete structure.

- Fleury, Georges Rohault. Gallia Dominicana: les couvents de St. Dominique au moyen âge. Paris, 1903.

- Lenoir, Albert. Statistique Monumentale de Paris: Explication des Planches. Paris: Imprimerie Impériale, 1867.

Bibliography

- Davis, Michael. “Fitting to the Requirements of the Place’: The Franciscan Church of Sainte- Marie-Madeleine in Paris.” in Architecture, Liturgy and Identity edited by Zoë Opacic and Achim Timmermann. Studies in Gothic Art. Turnhout: Brepols, 2011.

- Fleury, Georges Rohault. Gallia Dominicana: les couvents de St. Dominique au moyen âge. Paris: [publisher not identified], 1903.

- Hinnebusch, William A. The History of the Dominican Order. Staten Island, N.Y: Alba House, 1966.

- Jordan, of Saxony and Simon Tugwell. On the Beginnings of the Order of Preachers. Oak Park Ill: Parable, 1982.

- Lenoir, Albert. Statistique Monumentale de Paris: Explication des Planches. Paris: Imprimerie Impériale, 1867.

- Sundt, Richard. “Mediocres domos et humiles habeant fratres nostri:” Dominican Legislation on Architecture and Architectural Decoration in the 13th Century.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, Vol. 46, No. 4 (1987): p. 395-407.

- Sundt, Richard. “The Jacobin Church of Toulouse and the Origin of Its Double-Nave Plan.” The Art Bulletin, Vol. 71, No. 2 (1989): p. 185-207.