Louvre

Alan Carrillo, Kat McCall, and Patrick Nguyen

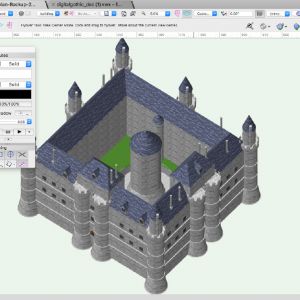

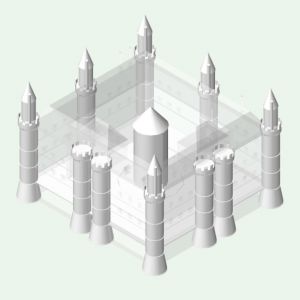

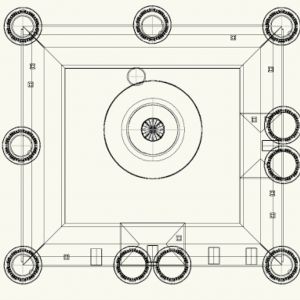

The Louvre castle was established as a defensive fortress in 1190 by King Philippe Auguste. Because its purpose was to defend against English invasion, it was designed for physical and symbolic strength, not beauty, and featured little in the way of decoration. It consisted of a cylindrical tower and a surrounding curtain wall. Construction on the keep, or donjon, preceded that of the curtain wall; both were likely completed by 1202, but some scholars suggest that it may have taken until as late as 1210 to complete the curtain wall. The donjon was built to a height of 30 meters, with a diameter of 15 meters and walls 4 meters thick. It was topped with a conical roof approximately 9 meters tall. Its surrounding crenellated and machicolated curtain wall was built on a nearly square plan measuring 72 by 78 meters. These walls measured approximately 15 meters in diameter and tapered to a stone base measuring 18 meters thick. Ten towers dotted the ramparts: one on each corner, one each at the center of the northern and western walls, and two each at the midpoint of the eastern and southern walls. A wet moat encircled the fortress while a dry moat, 9 meters wide and 6 meters deep, provided further protection to the inner donjon. Between 1230 and 1240, King Louis IX extended the western wing of the Louvre into the courtyard to make room for a set of modest administrative chambers and a small chapel, prompting the western wing to be named La Salle Saint-Louis in his honor. Under his reign, the Louvre’s donjon also became the stronghold for a sizeable portion of the royal treasury. Philippe IV, also known as Philippe le Bel, added rooms to the northern and eastern wings around 1315, reestablishing balance to the Louvre’s floor plan.

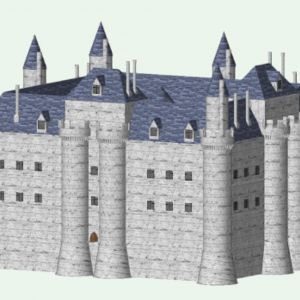

After a revolt in 1358 against King John II, his son Charles V began construction on the Louvre in an effort to reestablish both a physical and symbolic marker of the power and presence of the monarchy in Paris. He ordered the expansion of the city walls to accommodate for the growth of the city since Philippe Auguste’s original fortifications were built, and commissioned a full-scale renovation of the Louvre into a suitable and sublime royal residence. Charles V’s renovations to the Louvre were supervised by architect Raymond du Temple. These changes included the complete renewal and refurbishment of the north wing into royal apartments and a grand spiral staircase or grande visto access them, the installation of the remainder of the royal Treasury in the donjon, the addition of a second chapel in the north wing, restorations of La Salle Saint-Louis, and the addition of a third floor. Over a hundred windows were cut into the second and third story levels of the walls and the donjon; dozens of turrets and more than thirty chimneys and a gabled blue roof were added to provide the palace with an extravagant visage. The transfer of the Royal Library to the Louvre’s northwestern-most tower represented the symbolic transfer of wisdom and governance from the Palais de la Cité to the Louvre and established the Louvre as the central site of royal power and prestige in Paris. The evolution of the medieval Louvre can be seen in the archeological remains of the foundations of the castle, which were excavated in 1984 and remain extant beneath the Louvre museum today.

Selected Bibliography

Ayers, Andrew. The Architecture of Paris: an Architectural Guide. Lanham, MD: National Book Network, 2004.

Baldwin, John W. Paris, 1200. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2010.

Berty, Adolphe. Topographie Historique du Vieux Paris: Région du Louvre et des Tuileries. 2nd ed. Histoire Générale de Paris. Paris: Imprimerie Nationale , 1866. Accessed February 27, 2017.

Boussard, Jacques. Nouvelle histoire de Paris de la fin du siègede 888-886 à la mort de Philippe Auguste. Nouvelle histoire de Paris. Paris: Hachette, 1976.

Cazelles, Raymond. Nouvelle Histoire de Paris de la fin du règne de Philippe Auguste à la mort de Charles V: 1223 -1380. Nouvelle Histoire de Paris. Paris: Hachette, 1994.

“Château de Dourdan.” Castles of France. Accessed February 2, 2017.

Cruse, Mark. “The Louvre of Charles V: Legitimacy, Renewal, and Royal Presence in Fourteenth-Century Paris.” L’Espirit Créateur 54 No. 2 (Summer 2014): 19-32. Accessed March 10, 2014.

“History of the Louvre: From Château to Museum.” History of the Louvre. Accessed February 2, 2017.

Salamagne, Alain. “Lecture d’une symbolique seigneuriale: le Louvre de Charles V.” In Marquer la Ville: Signes, traces, empreintes du pouvoir (xiiie-xvie siècle), edited by Patrick Boucheron and Jean-Philippe Genet, 61-81. Paris-Rome: Publications de la Sorbonne, French School of Rome,2013. November 18, 2015. Accessed March 1, 2017.